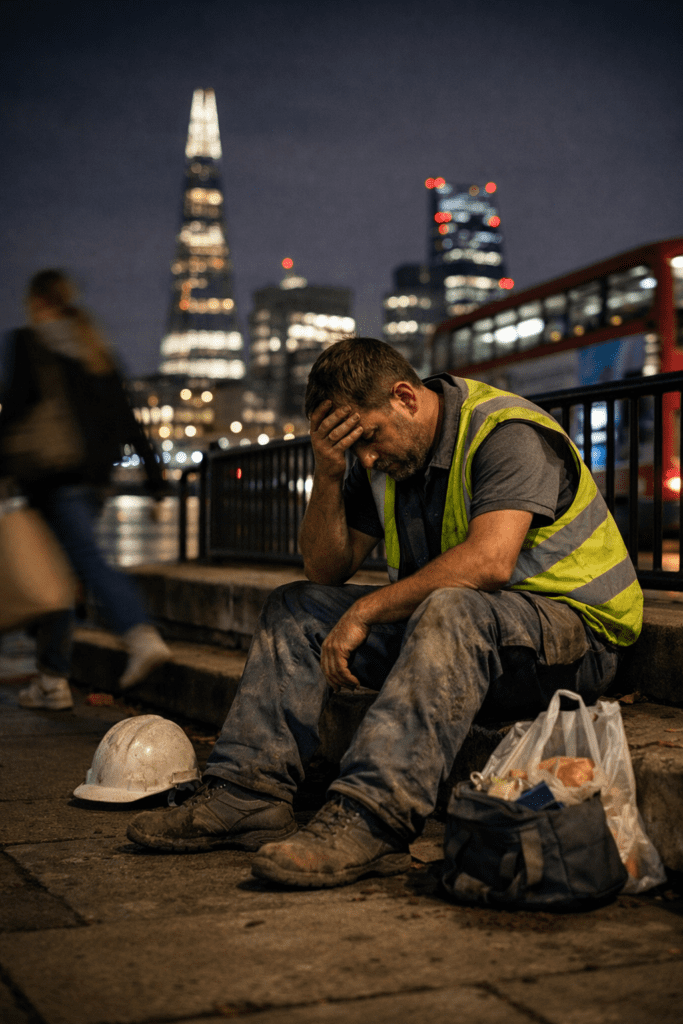

Having a job in the capital is no longer enough to escape financial hardship, with a growing proportion of London families falling below the poverty line even when one or more adults are in employment.

The phenomenon of in-work poverty has become a defining characteristic of London’s economy, challenging longstanding assumptions that work provides a pathway out of deprivation. Families across the city are discovering that paycheques cannot keep pace with the expenses required to live in one of the world’s most costly cities.

Wage levels tell part of the story. A substantial portion of London’s workforce earns less than the London Living Wage, the amount calculated to cover basic necessities in the capital. The problem concentrates heavily in sectors that keep the city operational—hospitality workers, retail staff, care providers and administrative employees frequently find their earnings insufficient for London’s cost of living.

The capital’s housing market compounds these pressures dramatically. London property costs rank among the highest globally, and even households with above-average incomes find themselves with reduced disposable funds once rent or mortgage payments are deducted. The housing expense burden creates a situation where many residents work extended hours or maintain multiple jobs simply to maintain their current position rather than advance financially.

Income inequality measurements reveal the severity of the divide. Once housing expenses are factored in, the highest-earning London households take home more than ten times what the lowest earners receive—a disparity markedly steeper than elsewhere in the United Kingdom.

Wage growth patterns over the past decade have failed to match inflation rates, according to assessments by city officials. This means numerous workers have less purchasing power now than they possessed years earlier, with the squeeze particularly acute outside the finance and technology industries where pay increases have been stronger.

The distribution of economic hardship follows clear patterns across London’s geography and demographics. Outer London boroughs report elevated rates of low-wage employment, while Black and minority ethnic residents face statistical disadvantages in accessing better-paid positions.

Employment sectors essential to London’s daily functioning—the very industries providing services residents and businesses depend upon—are among those least likely to compensate staff at liveable rates. This creates a sustainability question for the capital’s long-term economic model.

The two-tier nature of London’s economy has solidified into a structural feature. While finance, culture and innovation sectors generate prosperity for some participants, others navigate precarious employment, rising expenses and stalled earnings just to meet household requirements.

Addressing workforce inclusion barriers could yield economic returns for individuals and the broader metropolitan area. The question facing policymakers and employers is whether current patterns can continue without undermining the city’s position as a functioning global centre.